Türkiye 2/1/2020 - 2/9/2020 |

|

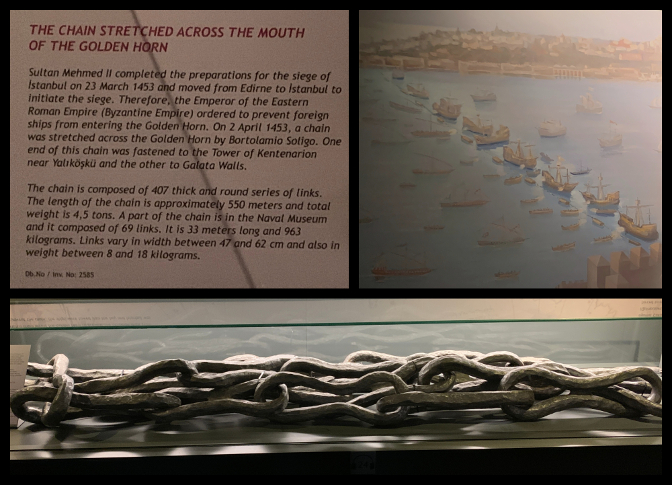

Wednesday 2/5/2020 - Topkapi Palace, Dolmabahçe Palace, Naval MuseumWe started the day with another fantastic hotel buffet breakfast: Eggs to order, pancakes, waffles, fruit, yogurts, fresh pastries, rice pudding, cheese, charcuterie, juice, coffee, sausage, falafel, hummus, bread, noodles, fried rice...and that's just a fraction of it. A great way to fuel up for another jam-packed day of sightseeing!After breakfast, as we were getting ready to leave the hotel, we saw a gorgeous sunrise over the Bosphorus from our window. Today's forecast called for rain, so we made sure to wear our rain jackets and bring our umbrellas. We met Toplum and Türker at 8:30 a.m. and drove back to the Sultanahmet section of the Old City. Our first stop was Topkapi Palace. Türker dropped us off behind the Hagia Sophia, next to the Fountain of Ahmed III. The Topkapi Palace was built in the mid-15th century by Mehmed the Conqueror, the Ottoman Sultan who conquered Constantinople. The palace complex and courtyards cover over 7.5 million square feet. It was lightly raining as we approached the Imperial Gate, passing a street dog stretched out comfortably on the cobblestones. As we entered the gate, we passed under the gilded tughra (calligraphic signature) of Mehmed the Conqueror. The palace grounds are divided into four courtyards, with increasing exclusivity. We walked along tree-lined marble cobblestone walkways amid lush green lawns in the First Courtyard. This early in the morning, we practically had the courtyard to ourselves. This area was open to anyone in Ottoman times. The Sultan would enter and leave the palace grounds via this courtyard. This courtyard is also known as the Courtyard of Processions because parades would take place here on Fridays. The Hagia Irene is located in the First Courtyard. This Byzantine church was commissioned by Emperor Constantine during the 4th century. When the Ottomans took control of the city, they neither destroyed the church nor turned it into a mosque. Rather ironically, they used it for storage of munitions. Now it is used as a concert hall. We caught a tantalizing glimpse of the Golden Horn, as the sun struggled to peek through the dark clouds. We entered the Second Courtyard passing through the Gate of Salutation. Its architecture seems influenced by western European castles; it looks straight out of a fairy tale. This courtyard was known as the Council-Justice Square. It was the administrative and ceremonial center of the palace, including the massive imperial kitchen complex. We entered a building which had golden grille work protecting its glass windows. This elaborately decorated building housed the Imperial Council Hall. Viziers, military judges, and administrative officials would meet here several times a week. A gilded lattice window (with no glass behind it) separates the Imperial Council chamber from the Tower of Justice next door. The Sultan could access this window from his chambers in the tower, which allowed him to eavesdrop on the council meetings unobserved. He would only address the Council if he disagreed with their approach. We crossed the courtyard to stop at the rest rooms, and it was absolutely pouring rain. We then minimized our outdoor exposure, heading indoors to the Outer Treasury building to view museum exhibits of arms and armor throughout history. No photography was allowed in the museum section of the palace. The extensive collection consisted of specimens from the 7th through 20th centuries. We saw amazingly decorated armaments and chain mail: Damascus steel blades, bows made from buffalo horn and wood, halberds, maces studded with precious gems, etc. We also saw the famed Topkapi Emerald Dagger, a.k.a. the Shah's Dagger. This dagger has a golden hilt inlaid with 3 large cabuchon cut emeralds and numerous diamonds. At the end of the hilt is an octagonal emerald on a hinge which reveals a watch. The dagger was commissioned in 1747 by Sultan Mahmud I as a gift for Nader Shah of Persia. The Shah was assassinated before the gift could be delivered, so this treasure has remained in Türkiye for the intervening 250 years. There was an entire exhibit of clocks and watches, which were all very ornate. Once we had finished in the museums, Toplum paid a separate entrance fee to allow us access to the harem. The harem is the location of the private chambers of the Sultan, his family, and their servants. A Sultan didn't marry; instead he had concubines. These were often young slave girls taken from the Black Sea area. Blonde caucasian women were preferred. They were educated in the palace and could rise up through the social hierarchy. Favored concubines had a fair amount of autonomy. They had their own money and they often had their own businesses at the Grand Bazaar. Once the Sultan died, his children from his concubines would fight to the death to see who would succeed him. The concubine who bore the victor would become the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan). The harem was staffed by "black eunuchs." The black eunuchs were slaves from Nubia. Because they had been castrated, they were trusted, and had tremendous responsibility within the administration of the harem. The eunuchs would conduct day to day business for the concubines, and would also act as teachers for their children. Each eunuch had his own private dormitory room and they were paid for their services. Eunuchs also had unique access to the Sultan, and could even influence policy. Though it seems difficult to believe that castration without any anaesthetic and a supposed 10% survival rate could have been enviable in any way, shape, or form, it is said that eunuch status was eventually coveted for the money and privileges that it could provide. The Chief Black Eunuch was actually the 4th highest ranking official in the Ottoman Empire. Although most accounts seem to state that the eunuchs were castrated at the age of eight in Egypt and then sold to the Ottomans, we also heard that some ambitious men who coveted eunuch status would father children at a young age before being voluntarily castrated. Then once the eunuch retired, the position was passed down to his son and so on. We entered the harem via the Gate of Carts entrance, and passed through the Domed Cupboards, a small room which was used for administrative purposes and record-keeping. The Chief Black Eunuch oversaw the business that was conducted here. Little natural light was coming through since it was so dark and rainy outside, so it was difficult to see in the brick interior. Then we entered the area of the harem reserved for the black eunuchs. These rooms and their courtyard were exquisitely decorated with 17th-century Kütahya tile. The tiles were painted in beautiful Islamic floral, geometric, and calligraphic designs in beautiful shades of teal and blue with golden accents. We passed through the Hall of the Ablution Fountain, where the black eunuchs would carry out their ritual bathing before entering the adjacent room: their own private mosque. In the Mosque of the Black Eunuchs, the beautiful hand-painted tiles were arranged into panels to form murals of Mecca. Exiting into the Courtyard of the Black Eunuchs, we passed under the golden arched Main Gate into a guardhouse. This was a room with larger-than-life gilded mirrors reflecting one another from opposite walls. This was integral to security. The black eunuch guards were able to see all angles of the room, to ensure that nobody was able to sneak into the harem. We followed the Corridor of the Concubines, a hallway with a marble shelf running the length of it. The black eunuchs would deliver meals to this shelf, and the concubines would serve the food within the harem. Next we passed into the apartments of the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan). Her rooms had beautiful tile work as well as murals painted to look like classical columns and Mediterranean landscapes. Window shutters were inlaid with mother of pearl in elaborate geometric designs. The harem was heated by fireplaces as well as strategically placed braziers. The Queen Mother's bedroom was heated by three fireplaces in adjacent rooms so that nobody had to enter her room to stoke the fire and she would not have to deal with smoke. The hammams (bathrooms) were exquisite. They featured indoor plumbing and gold-trimmed marble fixtures, including sinks, Eastern style toilets, waterfalls, and running water for showers. Muslims did not think that stagnant water was clean, so they did not sit in the large marble bath tubs; instead they sat on the edge and had water poured over them. Light came from overhead "elephant eye" skylights, and there were gilded cages in which the Sultan and Queen Mother could lock themselves while bathing so that they didn't need to fear attack when in this extremely vulnerable situation. Next, we entered the luxuriously appointed Imperial Hall, where the Sultan congregated with members of the harem for rituals, conversation, and entertainment. The hall was renovated in the mid-18th century and is decorated in a rococo style. The color palette consists of deep jewel tones, most notably red and blue. Tiles in this room are of Dutch provenance rather than Anatolian. The domed ceiling is the largest within the palace. A crystal chandelier hangs overhead, and gifts from heads of state (including a wooden clock from Queen Victoria) are on display. Musicians entertained the Sultan in this room. If women were in the audience, the musicians were blindfolded. We walked through a beautifully tiled hallway to access the Sultans' private chambers, entering the Privy Chamber of Murat III. This room retains its original interior design, dating back to the mid-1500's. The walls were decorated with beautiful blue, turquoise, and coral 16th century Iznik tiles. Light entered the room through stained glass windows. A regal baldaquin canopy bed occupied one light-filled corner. A marble fountain tucked into one of the wall niches provided background noise to prevent eavesdropping. The interior design in this room very much reminded us of Mughal architecture we have seen in India By the time we exited into the Courtyard of the Favorites, the rain had pretty much stopped. The Sultan's children would play here, and the princes were schooled by the black eunuchs in adjacent buildings. A patio here overlooks the Golden Horn. A stone-lined basin below the level of the courtyard was filled with water, and the favored concubines would enjoy punting here in small rowboats with a view down to the Golden Horn. We went back inside via the "Golden Road," a stone and brick corridor which received this moniker because the concubines would line up here for the Sultan to distribute gold to them upon his return to the harem. The Golden Road led us to the Mosque of the Harem. Unlike men, women aren't required to attend a mosque in order to pray. Nonetheless, a mosque was built inside the harem so that the concubines could pray there if they chose to. Sometimes imams were brought in to the Mosque of the Harem to give religious lectures to the concubines. The imam would sit behind a gold screen so that he could not see the women and vice versa. The interior design felt more feminine than other areas of the harem (with the exception of the Queen Mother's apartments); the mid-18th century tiles incorporate yellow colors, giving them a cheerful appearance. We returned to the Golden Road corrider, making a stop in the Kuşhane Kitchen. This was a small kitchen which was staffed night and day to provide food to the Sultan and his inner circle at any time. The staff of this kitchen would also accompany the Sultan when he left the palace to provide food for him on the road. The kitchen contained pantry shelves, a large fireplace and chimney, a stone basin sink with water taps, and a small powder room with Eastern style toilet and sink. The interior design of the harem chambers is eclectic. It consists of many different styles of tile work and painting added over the years. We exited the harem into the Third Courtyard. We entered the Audience Hall, where the Sultan would receive state officials and foreign ambassadors. In here were a baldaquin canopy bed and a respelndent golden throne. From the early 15th to late 17th centuries, the Sultan would forcibly conscript hundreds of boys each year from rural Christian villages under a policy of devşirme (blood tax). The Sultan would place these boys with Muslim foster families, where the boys would be educated and converted to Islam. After two years, the boys would return to Topkapi Palace. The brightest would continue their studies here at the Enderun School, studying literature, music, religion, and sports. They were groomed for administrative posts, such as tax collector or regional governor. Because these were Christian boys who had been indoctrinated into palace life, the hope was that they would be loyal to the Sultan, and could be trusted to not show favoritism to any other ethnic or geographic groups within the Ottoman Empire. When these boys matured and had children of their own, their sons were barred from these posts to prevent the rise of nepotism. The majority of devşirme boys became Janissaries in the Ottoman military. The Third Courtyard contained dorms, classrooms, and a library for the Enderun School. We entered the neo-classical Enderun Library (Library of Ahmed III). The library was built in 1719. It had a light and airy feeling inside, as it contained plenty of windows. The upper windows were embellished with stained glass, including glass delicately cut into Arabic calligraphic lettering. The lower windows had wooden shutters which were inlaid with mother of pearl and tortoise shell cut into geometric patterns. In between the lower windows were glass-doored cabinets which once housed over 3500 manuscripts. The walls were adorned with 16th and 17th century Iznik tiles. The ceilings were cream-colored gesso relief panels adorned with gilded floral and medallion motifs. The Sultan had his own personal reading niche. It was an inspiring place for learning. As we exited, we passed underneath a gold Arabic inscription above the door which reads, "My friend take learning seriously and declare, 'O my Lord, increase me in knowledge.'" The Fourth (and most exclusive) Courtyard was for the Sultan's relaxation, and contains lush pavilions along the Golden Horn. We walked across the Imperial Terrace toward the summer kiosk now known as the Circumcision Chamber. The interior is dim, with dark upholstery and dark 16th / 17th century tile work. The upper windows had delicate stained glass borders. Every surface of the room was decorated; the ceiling alone contained a dizzying array of fractal-like tiles. The decor was all symmetrical. The dark atmosphere probably made it into a cool refuge in the heat of summer. It has been known as the Circumcision Chamber since Sultan Ahmed III had his sons circumsized here. Next, we entered the Baghdad Kiosk. This pavilion was constructed in 1639 to commemorate Sultan Murad IV's victory in the Baghdad Campaign. It was used as a private library (and place of turban storage) for the Sultan. Once again, every available surface was intricately decorated. The lower windows had wooden shutters inlaid with tortoise shell and mother of pearl. Calligraphy flowed like a ribbon around the perimeter of the room on beautiful tile work. The upper windows had simple stained glass patterns. There was a copper fireplace and a plush throne, making this seem like a cozy private study for the Sultan. The outdoor terrace overlooks the confluence of the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn. We could see the Maiden's Tower and the 15 July Martyrs Bridge. Lastly, we returned to the Second Courtyard to visit the palace / imperial kitchens. These are huge brick structures that had the capacity to feed tens of thousands of people. Usually the staff "only" cooked for the ~1000 inhabitants of the palace, but for Islamic high holidays they would feed the entire populace. Each of the high-ceilinged chambers of the kitchen had a large central chimney overhead. Large copper cauldrons were situated in the enormous fireplaces. The kitchens are currently also being used as museum spaces, with glass cases displaying cooking implements, porcelain, etc. Copper was used to make cauldrons, pans, sahlep jugs, coffee pots, bowls, trays, and sherbet vessels. A technique called tombak utilized mercury to add gold plating to certain ceremonial copper objects. When all was said and done, we had spent around four hours exploring this massive palace. Toplum did an amazing job educating us about the palace's history, and putting it into context for us! Toplum asked what we would like to do for lunch. As we still had two additional stops on our itinerary in the Beşiktaş neighborhood, we said that we would prefer something quick, local, and informal. Türker drove us toward the Beşiktaş area, and Toplum asked him to stop at a restaurant in the Karaköy neighborhood. (I was initially quite confused because I was thinking of Kadiköy instead, which is located across the Bosphorus on the Asian side!) We ate lunch at Kadiköy Gulluoglu, a restaurant founded 200 years ago. This is a cafeteria-style restaurant where you order and pay, and then bring your receipt to various stations to collect your food. This place has been a favorite of Toplum's since his university days, and specializes in phyllo dough Turkish pastries and baklava. Craig and I ordered mincemeat in phyllo dough and a cup of Turkish tea. We went over to the phyllo pastry station, where a man looked at our receipts and cut us each a fresh hot slab of flaky phyllo pastry filled with savory mincemeat. He chopped it into squares for ease of eating. We then went to the tea station and collected our tea in tulip-shaped glass cups. We sat at a table and enjoyed our delicious and efficient lunch. You can tell that a restaurant is good when it is full of locals, as this one was. When we were finished, we got back into the car and Türker drove us the rest of the way to Beşiktaş Our next stop was Dolmabahçe Palace. It was built in the mid-1800's by Sultan Abdülmecid I, who felt that the Topkapi Palace that we had visited this morning was too old-fashioned, dark, cold, eclectic, and dated. He wanted a palace that was more European, symmetrical, airy, and modern. He certainly was successful in building just such a structure. The elaborate exterior of the palace, as well as its massive gates and clock tower, immediately called to mind the Winter Palace and Catherine Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia. I asked Craig to stand next to one of the massive wrought iron gate panels for scale. It absolutely dwarfs him in the photo. The palace contains 285 rooms, and is a mixture of baroque, neoclassical, and rococo styles. Fourteen tonnes of gold were used to gild the ceilings. The architects were so informed about the latest trends in European building that they installed a metal and glass roof at Dolmabahçe Palace several short years after such a roof debuted at the Crystal Palace in London. The palace was home to 6 Sultans. Once Türkiye became a Republic in 1923, its first President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk used the palace as a presidential residence. In the entryway of the palace, a cat was resting on a plushly upholstered bench, between classical columns and next to a gilded urn. I took a photo of this #kedi as Toplum was procuring our tickets. I was asked not to take photos once we entered the palace proper. It was a shame, but I always comply with photography rules. We knew that one of the claims to fame of this palace was an impossibly large Waterford crystal chandelier. As we first entered the Ambassador's Hall, we were impressed by a beautiful chandelier and tall sparkling candelabra made of Baccarat and Waterford crystal. They were dazzling, and I couldn't help but wonder how much effort they must have to expend to keep these so squeaky clean. We started out passing through the public areas of the palace, used for entertaining politicians and diplomats. As we walked from room to room, the chandeliers got even more elaborate. We found ourselves asking, "Is this THE chandelier?" There was even a grand staircase with balustrades made of Baccarat crystal. Next we toured the private harem area. Even with the Islamic proscriptions against art depicting the human form, paintings hung in the harem hallways depict Ottoman military victories, armies and all. In deliberate contrast to the eclecticism of Topkapi palace, with its add-ons over the centuries, Dolmabahçe Palace is absolutely symmetrical, front to back and left to right. This also applies to the furnishings; Tsar Nicholas I of Russia gifted a pair of bearskin rugs to the Sultan in order maintain this symmetry. One gift which could not be doubled, a pipe organ, was relegated to a chamber in the middle of the building, so it straddled the central axis providing symmetry. When we reached the ceremonial hall, we knew we were laying eyes on THE chandelier. There was no question about it. Above us, a Waterford crystal chandelier weighing 4.5 tonnes hung from a domed ceiling. They had to install metal bracing above the domed ceiling to support its weight. t was interesting to see the transition between the extremely Ottoman uniqueness of Topkapi Palace to the more European Dolmabahçe Palace. The former gives you a sense of what the Ottoman Empire was like, while the latter gives you a feel for modern Türkiye's relationship with the western world. Of course, the behavior of many of the tourists was quite disappointing. People blatantly ignored the prohibition on photography, which meant that the poor staff spent most of their time running after people and calling after them to stop taking photos. They seemed relieved that we were following the rules; so much so that one employee struck up a conversation with us, and said that he wished they received more tourists like us. We exited the palace and took some photos of the exterior of the building. As I took a photo of the Bosphorus through an elaborately decorated gate, a bird flew by. He is framed by the gate in the resulting photo. Türker then dropped us off right next door to our hotel, at the Naval Museum. I was excited to see it, since 20 years ago, my dear friend Beth and I toured the Turkish naval frigate Fatih during Sail Boston 2000. The officers were very hospitable, serving us Turkish coffee and raki. They acted as goodwill ambassadors. They gave us tourism brochures and encouraged us to visit Türkiye. Well, 20 years later, here I am! We passed some artillery and a huge ship's propellor and entered the newly renovated Naval Museum. The lower level of the museum is a gallery of boats. We first passed the lifeboat of yacht Savarona (which has been the Presidential yacht since the days of Ataturk). Next we came across an exhibit of three small wooden caïque boats in which Ataturk himself had rowed. The boats were displayed in front of photo enlargements of Ataturk rowing in them. These photographs are famous; they were deliberately used to depict Ataturk as a down to earth, normal guy. Perhaps the most impressive exhibit was the Historical Galley, which dates back to the 16th century. It takes 3 men to operate each oar, and there are 24 pairs of oars, for a total of 144 oarsmen. It is approximately 40 meters long by 5.5 meters wide. The Sultan would sit in the aft kiosk which was elaborately inlaid with mother of pearl, tortoise shells, and gems as he traveled in inshore waters. There were about a dozen Ottoman Imperial caïques dating back to the 1800's and early 1900's. Depending on the size, they had 5, 7, 10, or 13 pairs of oars. They were used by the Sultan and his family for ceremonial and excursion purposes. They were all decorated quite beautifully, with gold leaf and floral motifs. There were gilded figureheads such as lions and eagles. Looking out the window, we could see the window to our hotel room, right next door. After enjoying meandering through these massive and gorgeously decorated boats, we went upstairs. One interesting exhibit here was a section of the defensive chain which attempted to protect Constantinople from conquest. The massive chain measured 550 meters long, stretching from the Old City across the mouth of the Golden Horn to Galata. The 407 links weighed between 8 and 18 kg apiece, giving the chain a total weight of 4.5 tons. When the Ottomans attacked in 1453, they were not able to penetrate the chain. Instead, they towed their ships overland on the Galata side, gaining access to the Golden Horn waters from the north. The section of chain on display here is 33 meters long, with 69 links, weighing 963 kg. Other interesting items on display include historical navigation equipment, 16th century nautical maps, and a 16th century cannon. 16th and 17th century glass and terra cotta grenades looked more like decorative vases than artillery. We saw a bronze howitzer, and a bronze cannon shaped like a dragon that was taken at the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683. We saw a traverse board, with which we had not been previously familiar. This is a wooden board with peg holes in it, looking like a cross between cribbage and battleship. It served as a ship's log, with those taking the watch moving a peg in the appropriate direction on the board every half hour. This allowed sailors who were unable to read or write to contribute to the documentation on the ship's course. We saw a model of a frigate very similar to the one that Beth and I had boarded during Sail Boston. The model was of the Barbaros-class frigate Barbaros (F244) launched in 1993, and Beth and I had toured the Yavuz-class frigate Fatih (F242) launched in 1987. An exhibit showed the evolution of naval officer uniforms from Ottoman times to present day. The original uniforms consisted of robes and turbans of fur and silk. This evolved into navy blue doublebreasted suits with gold accents and a red fez, which evolved into modern military dress for men and women. The present day dress uniform was quite similar to what the officers on the Fatih wore in 2000. There was an entire room devoted to martyrs lost at sea. There were two emergency buoys belonging to submarines that had sunken. (ATILAY-1 and TCG DUMLUPINAR II) It was quite eerie to see these, knowing that they were released and rose to the surface, advising any vessel that finds it to use the enclosed telephone to try to contact the crew. If they don't answer, advise the next port. Ataturk's cabins from yachts are also on display here in the museum, belying that he did indeed enjoy the finer things in life despite his image as a man of the people. His VIP cabin from the original Yacht Ertugrul was cozy yet elegant, and the later Presidential Yacht Savarona contained large fancy furniture. Some of Ataturk's belongings were also on display: clothing, record albums and a leather RCA record holder, a pistol, a wristwatch, and some medals. We finished off our tour in the basement, inspecting early deep sea diving equipment (metal helmets, weighted boots, and manually operated air pumps). There was an announcement that the museum would be closing in 10 minutes, and we made our way to the exit. We had only been here for a little over an hour, but somehow we still managed to see everything, albeit briefly. Per my usual m.o., I took many photos so that I could do additional research afterwards. It was raining quite heaviluy when we were done for the day. We stood under the overhang in front of the museum and said goodbye to Toplum. He had dismissed Türker for the day when he dropped us off here. We just needed to walk a very short distance to the hotel, and we had our umbrellas and raincoats. We felt bad for Toplum, who had a 30 minute walk home ahead of him. We thanked him for another wonderful day and went our separate ways. Our legs and feet were tired from having been on them all day (the car rides and a quick lunch were our only times seated). And with the heavy rain, we just didn't feel like leaving the hotel to find a place to eat dinner. So we decided to eat at the hotel restaurant, Ist Too. Hotel restaurants are usually pricey, but the convenience was worth its weight in gold. Craig had a Bomonti malt beer, and I had the Turkish favorite spirit raki, an anise-flavored clear alcohol which turns a milky white when you add water to it. We had fresh baked bread with hummus and olive oil for dipping. Craig had an Adana Kebab (spicy lamb and beef kebab with bulgur rice and lavash bread) and I had a lamb and beef kebab wrap with fries. Everything was delicious and really hit the spot. For dessert, I had the caramel rocher ganache stuffed with caramel and covered with chocolate, served with vanilla ice cream and sprinkled with gold flecks. It was one of the most delicious and beautiful desserts I have ever enjoyed. When the waiter brought the check, I was amazed at how inexpensive the whole meal was. As I went to pay, the waiter realized that we were hotel guests, so he rescinded the check so that he could apply a discount. An appetizer, two entrees, two beers, a raki, and a gilded dessert ended up costing us under $50 including the gratuity. We were shellshocked. We really can't say enough to praise this hotel. It has been a joy to stay here. After posting some photos from the day and taking some notes, we went to sleep. Topkapi Palace Dolmabahçe Palace Navy Museum |

Sunrise over the Bosphorus First Courtyard, Topkapi Palace Gate of Salutation, Topkapi Palace Courtyard of the Black Eunuchs, Topkapi Palace Harem Imperial Hall, Topkapi Palace Harem Tiles, Topkapi Palace Harem Courtyard of the Favourites, Topkapi Palace Harem Toplum in front of the Baghdad Kiosk, Topkapi Palace  Tiles within Topkapi Palace Harem Dolmabahçe Palace Dolmabahçe Palace #Kedi Dolmabahçe Palace view of the Bosphorus  Turkish Frigate Fatih (F242), Turkish Frigate Barbaros (F244)  Defensive Chain, Naval Museum Glass and terra cotta grenades, Naval Museum Emergency buoy from the sunken submarine ATILAY-1, Naval Museum Dinner at Shangri-La Bosphorus See all photos from February 5 |

|

16th century Historical Galley at the Naval Museum Imperial caiques at the Naval Museum |

|

|

|

|

|